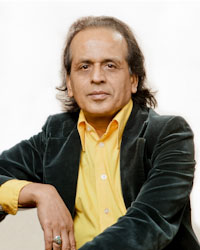

Note: This lecture was given the night that the Temple of Set was legally incorporated. Michael A. Aquino attended this lecture following submitting the corporate formation documents. Dr. Iyers would become his Ph.D. advisor.

In a time of confusion, constant change, and continual crises, we are ever tempted to elevate our tentative half-judgments to the status of finalities, closing the door to the future, limiting the possibilities of growth in others and in ourselves. The therapist, Carl Rogers, emphasizes the importance of unconditionality in human relationships and is willing to see beyond the apparent constants of human nature and into that mysterious underground in which the origins of the fundamental capacity to change are found. Can these germs, hidden within the depths of human beings, for change in themselves and in their lives, be the basis of communities, communes, conceptions of community, at several levels and in concentric circles, in a new and more intentional sense than any known in recorded history?

A community is any collection of human beings, diverse but more or less united, who share in common an unconditional and continuing commitment to ends, to values, to beliefs, or maybe only to procedures, but to such an extent that they can rely upon each other to render voluntary compliance with accepted obligations, and show that they are at least minimally capable of self-correction, self-expression and self-transcendence. Put in this large and exacting way, a community is as utopian as the ideal man or the ideal relationship. But to the extent to which every human being is constantly involved in some kind of correction from outside, in his environment, he engages in criticism of others which is often only his own way of criticizing and defining himself. To the extent to which everyone sees through formal laws and coercive sanctions and recognizes some alternative among friendships or an easier, more natural, trustful context in which he can free himself and grow, to that extent human life is larger than social structures, and man is vaster than all the classifications of man. There is a deep sense in which the large definition of the community is close to some element in every one of us – an element which cannot be abolished, cannot be invalidated, does not owe anything either to laws or institutions or constitutions, which sees beyond our parents and teachers and our environment, which includes lonely moments of bewilderment before the vastitude and versatility of nature. There is something in every human being which makes him want, seemingly, to get to the top of some professional scale but deep down only represents a desire to get to the top of a mountain, his own inward journey to some invisible summit from where he can see his life – if not steadily, at least less unsteadily than at other times; if not as a whole, at least sufficiently as a whole to make sense to himself and have self-respect as he recognizes and approaches the moment of death.

What we are witnessing today is a fragmentation of consciousness, more clearly seen in the structure of our society, towards which the whole world is tending: an excessive increase of roles, complexities, rules, pressures of every sort, such that human beings even with enormous social mobility cannot meet the challenge from outside because of inadequate psychological mobility. The contemporary revolution is elusive partly because of its insistent stress on flexibility against the rigidity of educational institutions, religious institutions, and political institutions. On the other hand, while we wish to be flexible, open-ended, willing to change, the very pace of change makes us want to do more than merely adapt. We are looking for a basis of continuity amidst the flux. Human beings, when their fragmentation of consciousness becomes insupportable, seek either through meditation or through music, through silence and solitude, if not through traditional forms of worship and prayer, through self-created rituals and rites of the sacred, to find a way by which they can dig into the very depths of their potential being. They thereby hope to tap latent energy so that they can have a tangible, ever existing sense of the unlimited at the very time when limitations are pressing.

The whole of American history, over two hundred years, has been not merely some sort of homogenized search for a national community. There was much more to the American Dream, which was understood not only by the so-called successes but perhaps even more poignantly by the failures – all the many immigrants who came to set up communes and communities, which no doubt eventually died, but who still somewhere felt that what these efforts represented was something real with a possible meaning for other human beings. There were over a hundred communes involving about a hundred thousand people. Of these, very few, like the communities of the Shakers, lasted for over a hundred years. The Rappites continued for almost a hundred years; the Icarians lasted for fifty years; but there were many, many more which were transient, dying almost within a few months after they were born. In all of these there was an assertion of an impulse which might have been premature, in certain respects, might have been misconceived and mistaken in the narrowness of the basis of allegiance or the degree of reinforcement through controls. But nonetheless they represented a kind of daring, a defiant and sometimes desperate assertion of freedom that is part of the American Dream.

If we look at all of these social experiments not only in terms of what went wrong, but also for what we could learn from them, there are certain lessons that could be drawn. These are not merely abstract lessons but rather concrete lessons that are now again being learnt by those who over the last ten years have attempted every kind of communal, semi-communal and mere transient, nomadic form of existence. One of the lessons, said Arthur Morgan, looking at these communities, was the fact that they were exclusive, that they were not universal. There are, of course, very few people anywhere on the globe who can rise to that ultimate affirmation of the American Dream represented by Buckminster Fuller. At a time when doomsday seers talk in quasi-racialist language, reinforcing the same age-old fear of the whole and of diversity, Fuller insists that no utopia will ever be real or valid unless it is for all, unless it is for the hundred percent of human beings who live on the globe. He adds that the resources of the world today are used on behalf of about forty-four percent, but unless and until they can be used for all, there will be no Kingdom of Heaven on earth. Does this mean that any one community, any one communal experiment, must take on the burden of all? Does this mean that there must be a once-and-for-all, total change in the social structure? This was a natural thought for many pioneers of communes who felt that they would show the way to others, but they ignored their predecessors and their successors. When they came to America, they forgot timeless truths concerning the continuity of human history and of individual life – that birth and growth are inseparable from suffering and death; that the whole of life must accommodate a preparation for the moment of death and also welcome the moment of birth of other human beings; and that there is not merely togetherness in space but also a community over time. And there are many orders of time. At one level time is merely the succession of events; at another level it marks the transmission of ideas that cuts across purely temporal divisions or the historical delimitations of epochs.

If we try to draw lessons from the old communes, we might say that they were attempting something very real on a local plane. They wanted to be universal, but because of the intensity of isolation from the rest of the community – which was more possible in America than in Europe – in time these communes became unself-critical. There was no principle of negation built into the very structure of the community, so indeed people were prey to the very same desire which we find everywhere in modern society – the concern to settle down and find bourgeois stability and respectability.

Now, what was distinctive to California? As early as the late nineteenth century Josiah Royce could see California essentially in terms of social irresponsibility and sloth, indolence in a sunny climate and the impossibility of getting people to be truly cultivated, to do anything which required concentration. This was the sybaritic, hedonistic image of California which one still gets, of course, in other sectors of the United States. But there were also other voices. There were those who felt that California was not merely to be assimilated into some Mediterranean mythology; that there was something else involved here, which was a richer mixture and a greater ferment than elsewhere; and that it was a logical culmination of the American Dream. After pioneers had reached the limit of physical settlement, there was another kind of pioneering involved in another kind of journey. Whitman put this in his characteristic way, very broadly and boldly. He said that when he came to California he asked the question, “What is it that I started a long time ago and how can I get back to that?” It is a venture into the interior realms of consciousness, digging into the very depths of one’s being, going beyond ancestral ties, racial affinities, cultural and social conditioning. It is the asking of deeper questions. Others saw this in terms of a mix of North and South, Latin and Anglo Saxon, East and West – much more evident in our own time – and a mix of many other kinds; also of Europe and America.

The history of California, even more perhaps than the history of the United States as a whole, is a history of lost opportunities, of misfired innovations. It is a history of intellectual and spiritual abortions in a state where in some years there are more physical abortions than births, more divorces than marriages. How then, in such a California, can we get excited and be credible to each other even in talking about the community of the future? Here let us invoke Plato who, when he spoke of Koinonia, said that a community involves a sharing of pleasures and pains. When Californians are sharing pleasures, for what they are worth, they are quite forgetful of communities. But when they share pains, they experience an immense void. When they experience post-coital sadness, when they experience the pain after every new wave of gush and excitement, when they experience that deep discontent – which may not always be divine and may sometimes indeed be demoniac – they know that there is something more.

This is reminiscent of what was said by a Sufi sage when one of his students asked him, “Why is it, O Master, that when people come to you for discourses, for teaching, for lectures, saying they really want enlightenment, you merely get them to become engaged in some activity?” The Master replied, “Very few of those who think they want enlightenment want anything but a new form of engagement. And very few of those who will get engaged will get engaged to the point where they can see through the activities, because they will get so totally consumed that they will have no opportunity to see beyond. But those few who are confident in their engagements know that they do not need to put themselves totally into them and can see limitations. They will say there is something beyond.” They do not know what that something beyond is, but they are certain that there is something beyond. And when they are ready to maintain in consciousness that conception of something beyond, then they are ready for those processes of training that might lead to enlightenment.”

California too is to be characterized not only by successes but also by its failures, and these failures prepare it for that ultimate hubris which is still the privilege of the American – to think big, to cherish the impossible dream, to ask whether even in the provincial town of Santa Barbara something profound can emerge. Whittier may have been extravagant rather than wholly wrong when he said that here could be the second founding. But this could be a very different kind of “founding” from what can be historically dated or blazoned forth by the national media. This is perhaps the most important lesson we might learn from the failures of the past decade. A few understood at the very beginning of the Hippie movement that the moment it was bombarded with publicity it could be killed even before it really got going. The early flower children were instinctively right in regard to the logic of inversion. Society had reached a point of such absurdity that one had to invert everything. Teachers were no longer teachers; parents were not really parents; scholars were usually not scholars. One had to allow each one to have his own ego games, while at the same time insisting that no one was taken in by any kind of phoniness. Many were desperately concerned to find some authentic meaning which could be sustained through trust, openness and love shown concretely in everyday relations. The innocents were right in their perception of the logic of inversion, but, of course, they could not stay apart from all the institutions, all the efforts to capture and formulate what they were doing. Above all, there was the insoluble problem of new entrants, which was also the problem of the old communes in America and in California. What can be done about new entrants? Either one closes the community to all new entrants, in which case we get a boring uniformity of belief and practice as well as intense mutual bitchiness, or we open the community to new entrants and every fresh wave will produce a dilution of what was there in the beginning.

This is a problem of every society, but also a problem that is peculiarly American because of the logic of assimilation, the logic of homogenization. The constant inflow of new entrants is part of the meaning of America. In that sense, it must always aim at the sky – at universality – despite all the tired old attempts to limit America to some narrow view of a Judaeo-Christian succession to the Roman Empire. Historically and philosophically, America is that country in which every man can define himself and take what he needs from the world’s heritage. It is that country in which each man can make his own authentic selection out of the entire inheritance of humanity. If he is not helped by his schools or his parents to exercise his privilege of individuation, he must self-consciously negate the conformist culture of Middle America. The first step for many today is to come loose, to try to shake off the hypnotic hold of an up-tight structure of transmitted prejudice. This is irreversible and is increasing every year. Even people who are apparently cosy in their middle aged, middle class existence are getting affected through their children by this determination to come loose. This is a painful step, a necessary break with the recent past. Of course it has produced a great deal of chaos, but that is no worse than the visible muddle of institutions that proliferate rules but are inefficient and no longer work fairly or properly. Truly we could say that the whole formal structure today makes America curiously less efficient than many other countries of the Old World.

In this context, and with the hindsight of some lessons learnt from two hundred years of American history, as well as a few from the last ten years, we might well ask about the community of the future. The community of the future would require a rethinking of fundamentals – the allocation of space, the allocation of time, the allocation of energy in the lives of human beings. It will have a macro-perspective and at the same time a micro-application. It may tie up with old and new institutions, but essentially those who enter into such communities will see beyond institutions. Some may drop out, others may cop out, and there will be those who are psychologically at a critical distance from their jobs, schools, and the entire system – psychologically outside even though for the sake of livelihood they may be inside them. There would also be those who have the imagination and the determination to create, with a minimum means, sometimes merely by throwing away excess or by juxtaposing skills that otherwise do not come together, experiments in new kinds of informal institutions.

It will take a very long time before we can really arrive at self-regenerating institutions. No society had a secret in regard to self-regenerating institutions, but there were other cultures which knew something about longevity. America knows many things, but it has still to learn the secret of institutional longevity. It took much effort from Plato to prepare the foundation for an Academy which lasted nine hundred years. In the thirteenth century groups of individuals in England set up houses, monasteries and small colleges which became the University of Oxford, which has lasted for so many centuries with some fidelity to what was there from the beginning. Americans are not unaware of the significance of such facts. Today when everything is so fragile and transient, and when they are willing, unlike earlier generations, to ponder the fact of death, they are also willing to discuss immortality on philosophical and not merely religious terms. They are now ready to find ways in which they could self-consciously thread together moments, days, weeks, months and years in their lives, and they are searching. The search is intense and poignant because there are so many mistakes, so many misfirings. And at every point, there is a re-enactment, a repetition of the same problems which are embedded in the existing structure.

One way of considering how new allocations of space, time and energy will eventually emerge is by seeing all institutions, the whole structure, in terms of a series of concentric circles. There is the inner circle of those who take decisions. We may call it the Establishment, though fortunately there is no real establishment in America which believes in itself. There is still the core constituted by those who control power and take decisions, and this is true at many levels. Outside that ring there is a large number of followers, people who are often apathetic, who seem blindly to go along, and some who will even think it unpatriotic to question decisions taken by central agencies. In the outer circle beyond the second, there are the negators and the critics. We might call them radicals and they may see themselves as revolutionaries, but essentially they are people who are more concerned with talk and analysis than with action and example. They are also the victims of the same social structure which they seek to negate and reject. These negators are nonetheless important and they certainly have played an indispensable role in the last ten years.

But beyond the negators there is still another ring in which are those who are willing to be quiet for a while, who are willing to move away from the limelight and to be engaged, to be fully occupied and even fulfilled at some level, in pioneering new ways of living, new ways of sharing. This could range from communal householders who simply learn to beat inflation by sharing their uses of time, space and money, to those who explore new avenues for the constructive concentration of energy. In this sphere we might also include people who merely get together to listen to music or to meditate. There are also those who are concerned with bolder and more ambitious experiments on a larger scale on vast farms and estates. In all of these circles the problem will persist which exists in every kind of structure. How is it possible to ensure an unconditional commitment to shared values and also to persons as sacred, an allegiance to the forms and not to the formalities?

How can we ensure that people will gain confidence in using rules so precisely that they will also have rule scepticism built into them, because they know that no general rule could ever fit a unique situation? People can conceivably gain so much confidence in the fulfilment of particular roles that they can also afford to show role flexibility and even to exemplify role transcendence. To take a simple example, we might find a man in the county administration or in a permit office who knows all the tortuous intricacies of legislation, but reciprocates an attitude of trust and is ready to show a layman how to cut corners. He knows the rules well enough to be confident that he is not violating them, but he also sees that they can be subserved and still leave room for legitimate manoeuvre, for freedom of action. To some extent this has always gone on in every society. Human beings don’t have to be told to be informal. Human beings don’t have to be told to see beyond laws and rules, because otherwise they could not fill up the large areas of human life which are unstructured. But where human beings become self-conscious – and this is a function of confidence in one’s ability to operate the structure – they can combine precision with flexibility, mastery with transcendence.

Strange as it may seem, the most crucial factor of all in individuation is actually the immanence of death and the readiness to see through the incessant talk of catastrophe to the constant reminder of suffering that is inescapable from life. This is crucial to the present and future maturation of the American mind, but it does not involve anything that would sacrifice what is quintessential to the American Dream. Indeed, it is a kind of growing up which may for the first time make the vision of the Founding Fathers meaningful and relevant, outside the formal apparatus of rules and institutions, to creating not islands of instant Brotherhood but new areas of initiative with unprecedented avenues of commonality hospitable to the making of discoveries and the enrichment of the imagination. This demands, above all, a breaking away altogether from the very obsession with success and failure which is so corrosive to human consciousness, the obsession with external status.

Santayana, who was not an American by birth or at the time of death, thought a great deal about the American experiment and continued to ponder when he came to California. Basically he saw America as a contest between the aggressive man and the genteel woman. This sounds strange today, but it is historically very important and is relevant even now. Again and again men emerged who, though aggressive, were the purveyors of the creativity that is at the core of the American impulse. There were also women, from maiden aunts to wives, who naturally sought security, but also wished to become sophisticated, to become what they thought Americans were not. In this kind of tension between the male adventurer and the bourgeois lady, there was a constant peril to the creative impulse. A Marxist-Leninist would put this in a different way, and speak of “the bourgeoisification of the proletariat.” Here came the world’s proletariat, but as they became bourgeoisified, they forgot the deeper impulse behind America – which has nothing to do with class or status or structure, which has to do with the wanderer, the nomad, the free man. The original impulse became obscured, perverted into a false nationalist sentiment, a substitute for true feeling, a flight from real experience of the wide open spaces and their equivalents in the human mind.

Santayana thought that California, for the very reasons that others criticized it – its lack of gentility, its crudity, its slothfulness – would not permit maiden aunts and stylish women to set the pace. It was impossible in California for gentility to come up on top and eliminate the creative impulse. He also thought that, whereas elsewhere in America people came to exchange the strong Transcendentalism of the early years for a wishy-washy admiration of nature, here in California when people went to the Sierras they felt something deeper, a negation of argument, a negation of logic, a sense of the vanity of human life and the absurdity of so many of our structures and relationships. Nature here in California made people think beyond America itself. It made them have larger thoughts about human frailty and the fragility of human institutions in relation to the whole.

This may well be deeply relevant to the future. The future, philosophers tell us, will never resemble the past. The future is indeed much larger than the past. If one takes man’s age for about twenty million years and puts it into a twenty-four hour scale, six thousand years of recorded history do not amount to half a minute. Who is entitled, on the basis of what we already know about the age of man, to set limits on the future? When people set limits on the future, history is finished for them, but not for others. There are many people today who are willing to cooperate with the future, who are not threatened by the universal extension of the logic of the American Dream to the whole of humanity, and who are also willing, despite past mistakes, to persist and to continue to make experiments in the use of space and time and energy. One day, maybe even in our lifetime, perhaps around the year 2000, there might well be those who, remembering these trying times of subtle pioneering in the surrounding gloom, could say without smugness:

We dreamers, we derided

We mad, blind men who see

We bear ye witness ere ye come

That ye shall be.

Lobero Theatre, Santa Barbara

October 20, 1975

Hermes, July 1976

by Raghavan Iyer