The expanding Church’s experience in the late Middle Ages created encounters with many hold-over features of pre-Christian tradition and many aberrations to the Faith due to isolated developments. This would coalesce at the start of the Early Modern Period into a concern about rural folk who were in league with the Devil, known as Witches.

Anthropologists such as Rodney Needham see beliefs in malevolent sorcerers who may or may not be aware of their condition as such as a near-universal feature of human cultures. In much the same way anthropologists have generalized the term Shaman to denote a specific type of universal ritual specialist, they have also universalized the title of Witch for these malevolent sorcerers. The notion of Witches as malevolent magicians goes back to Greek sources and had a significant explosion during the Roman Empire, only to vanish for the most part during the Middle Ages. In the Early Modern Period, this universal feature, combined with Classical sources and Biblical notions from Revelation, would suture together as the notion of Witches and Witchcraft being a pervasive, underground movement in European culture. For a complete introductory account of this phenomenon, see Witchcraft: a Very Short Introduction by Malcolm Gaskill for the Oxford University Press.

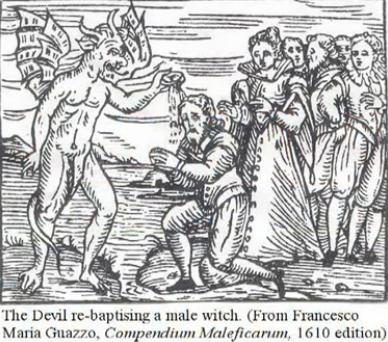

Unlike the Righteous Scholar Magicians working with the Hermetica, Witches were seen as being in league with Satan himself. Through renouncing the True Faith in favor of the unholy sacraments of the Devil, the Witches became part of a community that had done the same as He, pursuing their own independent ends (telos) against those of God. A complex mythology fusing ideas from Late Antiquity, including the accusations against Christians of child sacrifice and ritual murder, with remnant ideas from Paganism, emerged outlining the practices of Witches, with Malleus Maleficarum being the essential text in this genre.

This notion of the Witch combined rampant misogyny fueled by fear of mature, sexually independent women with the relatively new belief in the Secret Rule of Satan. Where the Righteous Magician Scholars were primarily men of high social standing, most of those accused as Witches were women. Typically they were considered “elderly,” which could mean anything from late 20s to 40s, and were unattached to a male figure either from never marrying or being a widow, making them potentially sexually autonomous. Fears of what sexually autonomous women might engage in for their own desires became fears of how Satan might use their licentiousness against the One True Faith.

To account for the failings of the Faith, or its Reformations, suspicion turned to dissension within the Faith’s own ranks. In addition to the fear of Witches amongst lower-status peasants, an equally disturbing image of such people being in positions of power also emerged. While far more rare than accusations against the powerless, those with tremendous power would sometimes be accused of being Witches and thus in league with the Devil. Gilles de Rais, Urbain Grandier, and others would follow in the footsteps of Pre-Modernity’s diabolically accused Knights Templar in being executed for their supposed allegiances to the Devil.

The fear of Witches and those in league with the Devil would permeate the Early Modern Period. As the communities of Christians began to splinter, these accusations would increase tremendously, inspired by a belief that these splinter groups were not fulfilling prophecy due to forces working directly against them. The new construction of Satan, thanks to the Witch Craze, would combine the action of the Witches at the lowest rungs of society with the high-level subversions of Faith being seen, real or imagined, by the opposition within the Christian faiths.